The latest version of the proposal to restrain community comment at school board meetings is at least not facially unconstitutional, so that’s a step in the right direction, I suppose. I like that it allows everyone to speak at the beginning of the meeting, rather than wait around for hours until the board reaches that particular agenda item. I’m not even against some limitation on how much a person could speak, though four minutes per person per meeting is too stingy. But cutting off all comment after an hour is awful. That means as few as fifteen people might be allowed to speak, no matter how controversial the agenda. (Yes, the board could entertain additional speakers at the end of the meeting if “necessary,” and if anyone waits around that long. But what are those speakers going to do, address issues the board has already voted on?)

If the board members want to make their meetings shorter, they should start by cutting the ceremonial photo-ops and check presentations, etc. Committees could submit their reports in writing in advance, and the board could discuss them only if there’s a need. Ditto with administrative PowerPoint presentations. Use the meeting time for things that actually require the presence of board members and the public together in a room.

Some board members are obviously tired of turning the mike over to the district’s critics. They seem to have realized (at long last!) that they can’t actually regulate the tone of people’s comments or prohibit harsh criticism, so the new solution is simply to cut the number of people who are allowed to speak. Yet on several issues—for example, Martin Luther King Day, the Raptor Visitor Management System, and the new bell schedule—the criticism at community comment seemed to make a difference in what the board did. If it can lead to better policy decisions, why cut it off?

School board meetings should be public meetings, not pep rallies, award ceremonies, or advertisements. The board shouldn’t see its job as managing the district’s image, which just comes off as manipulative anyway. Make good policy decisions and the image will take care of itself.

.

Tuesday, June 23, 2015

Wednesday, June 17, 2015

Report from the Hoover listening post

There was a listening-post-ish meeting tonight about the future of Hoover Elementary School, with school board members Chris Lynch and Orville Townsend responding to questions and comments from people concerned about the issues around the planned closure of Hoover. I counted about 70 attendees, including four school board candidates. I thought it was a good meeting. Here are some of the things I think the board members can take from it:

1. A lot of people are dismayed and upset by the Hoover closure and by the process that led to it, and continue to find the explanation of it incomplete and unconvincing. Lynch did his best to state some kind of rationale for the closure, but he also noted that he wasn’t on the board when the decision was made, so there was a sense in which he was trying to explain some other group’s decision. The audience reacted to each of the points he made with well-reasoned rejoinders, which was important for Lynch and Townsend to see. I know how strongly Lynch supports the larger facilities plan, and I have to believe that he wishes he had better answers to these questions.

2. People aren’t buying the district’s line that the elementary-age population of the Hoover area is declining. If there’s a decline in enrollment, it will be because of the closure, and it can be prevented by simply reversing the closure. Many speakers said that there has actually been an influx of young kids into their neighborhoods; that’s certainly true in mine, and Hoover’s pre-registrations for kindergarten next year are up significantly from this year. If the school stays open, there will be ample kids to fill it, no matter how the attendance zones are redrawn. (See this post.)

3. Several people (including me) spoke about how the district needs to recognize the effects of a school closure on the surrounding neighborhood and on the city of Iowa City. As one person said to me after the meeting, not every university town has the kind of thriving central neighborhoods that Iowa City has, and we can’t take them for granted. The school district should be proactive in supporting the neighborhoods in the core of Iowa City, the health of which has an effect on all of the surrounding areas.

4. Several speakers raised the teacher transition issue. Recently the administration told the teachers at Hoover that they would not be moved as a group to the new East Elementary School (a/k/a “Hoover East”) or given hiring preference there. This means that even the teachers who want to stay at Hoover until it closes will feel a lot of pressure to start looking for positions elsewhere sooner rather than later, since they can’t know whether anything will be available for them if they wait. This is a recipe for slow decline and death for Hoover, which, even if it closes, is still the elementary school for hundreds of kids for the next four years. The board members seemed relatively unaware of this issue and said that they would bring it back to the full board for discussion.

5. Some speakers raised the issue of the bond. To follow through on its facilities plan, the district needs to pass a $100+ million-dollar bond just a couple of years from now. It was clear that some people at the meeting were inclined not to vote for the bond if the plan included the Hoover closure—if not because of the closure itself, because they see the closure as part of a broader pattern by the district of dismissiveness toward community input. It was also clear that others at the meeting thought it was terrible that anyone would vote against the bond for that reason.

I don’t speak for the Save Hoover Committee, but I feel strongly that the group should be focused on the coming board election and should not take the stance of threatening a bond proposal that hasn’t even been drawn up yet. That said, however: You don’t have to be Nate Silver to know that the bond is less likely to pass if it includes a school closure. Please read that again: I didn’t say it shouldn’t pass, I said it’s less likely to pass. Some number of voters will be alienated by a school closure, and no amount of disapproving head-shaking will change that fact. Passing a bond is about putting together a coalition that will get you to 60% of the vote. It’s a negotiation with the community, and any clear-eyed supporter of the bond would approach it that way. Keeping Hoover open makes sense as good policy, but it’s also just smart politics for a district that needs to build that kind of coalition.

What can the attendees take from the meeting? I thought there were good reasons to be encouraged about the future of Hoover. Lynch, the chair of the school board, acknowledged that although the closure is part of the current plan, plans can change as circumstances change. He emphasized in particular that if the enrollment projections change, the board will need to reassess the plan. Although I think the board needs to scrutinize the enrollment projections more closely and needs to be proactive and not just reactive about sustaining its existing schools, I see Lynch’s statements as an opportunity, and I think there is good reason to believe that, over the next year or two, the district will realize that it needs to keep Hoover School open.

.

1. A lot of people are dismayed and upset by the Hoover closure and by the process that led to it, and continue to find the explanation of it incomplete and unconvincing. Lynch did his best to state some kind of rationale for the closure, but he also noted that he wasn’t on the board when the decision was made, so there was a sense in which he was trying to explain some other group’s decision. The audience reacted to each of the points he made with well-reasoned rejoinders, which was important for Lynch and Townsend to see. I know how strongly Lynch supports the larger facilities plan, and I have to believe that he wishes he had better answers to these questions.

2. People aren’t buying the district’s line that the elementary-age population of the Hoover area is declining. If there’s a decline in enrollment, it will be because of the closure, and it can be prevented by simply reversing the closure. Many speakers said that there has actually been an influx of young kids into their neighborhoods; that’s certainly true in mine, and Hoover’s pre-registrations for kindergarten next year are up significantly from this year. If the school stays open, there will be ample kids to fill it, no matter how the attendance zones are redrawn. (See this post.)

3. Several people (including me) spoke about how the district needs to recognize the effects of a school closure on the surrounding neighborhood and on the city of Iowa City. As one person said to me after the meeting, not every university town has the kind of thriving central neighborhoods that Iowa City has, and we can’t take them for granted. The school district should be proactive in supporting the neighborhoods in the core of Iowa City, the health of which has an effect on all of the surrounding areas.

4. Several speakers raised the teacher transition issue. Recently the administration told the teachers at Hoover that they would not be moved as a group to the new East Elementary School (a/k/a “Hoover East”) or given hiring preference there. This means that even the teachers who want to stay at Hoover until it closes will feel a lot of pressure to start looking for positions elsewhere sooner rather than later, since they can’t know whether anything will be available for them if they wait. This is a recipe for slow decline and death for Hoover, which, even if it closes, is still the elementary school for hundreds of kids for the next four years. The board members seemed relatively unaware of this issue and said that they would bring it back to the full board for discussion.

5. Some speakers raised the issue of the bond. To follow through on its facilities plan, the district needs to pass a $100+ million-dollar bond just a couple of years from now. It was clear that some people at the meeting were inclined not to vote for the bond if the plan included the Hoover closure—if not because of the closure itself, because they see the closure as part of a broader pattern by the district of dismissiveness toward community input. It was also clear that others at the meeting thought it was terrible that anyone would vote against the bond for that reason.

I don’t speak for the Save Hoover Committee, but I feel strongly that the group should be focused on the coming board election and should not take the stance of threatening a bond proposal that hasn’t even been drawn up yet. That said, however: You don’t have to be Nate Silver to know that the bond is less likely to pass if it includes a school closure. Please read that again: I didn’t say it shouldn’t pass, I said it’s less likely to pass. Some number of voters will be alienated by a school closure, and no amount of disapproving head-shaking will change that fact. Passing a bond is about putting together a coalition that will get you to 60% of the vote. It’s a negotiation with the community, and any clear-eyed supporter of the bond would approach it that way. Keeping Hoover open makes sense as good policy, but it’s also just smart politics for a district that needs to build that kind of coalition.

What can the attendees take from the meeting? I thought there were good reasons to be encouraged about the future of Hoover. Lynch, the chair of the school board, acknowledged that although the closure is part of the current plan, plans can change as circumstances change. He emphasized in particular that if the enrollment projections change, the board will need to reassess the plan. Although I think the board needs to scrutinize the enrollment projections more closely and needs to be proactive and not just reactive about sustaining its existing schools, I see Lynch’s statements as an opportunity, and I think there is good reason to believe that, over the next year or two, the district will realize that it needs to keep Hoover School open.

.

Monday, June 15, 2015

Putting the schools where the students are

In my last post, I wrote about why it makes sense to open the two new east side elementary schools below capacity and allow them to grow as their neighborhoods become more developed. One of the main reasons to do so is that it those schools cannot be filled immediately without using very disruptive rezoning contortions.

One way to see why that’s true is to look at the district’s student density map. It’s worth clicking on that link and perusing the whole thing. But here are a few highlights. First, here is an overhead view of the area around newly-built Alexander Elementary:

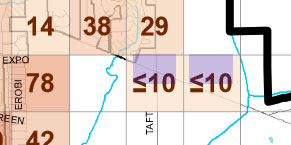

On the density map, it looks like this:

(The numbers represent number of elementary schoolers in each square; the more students, the darker red the squares are.)

Here is the area around the future site of the East Elementary:

On the density map, it looks like this:

Here, by contrast, is the area around Hoover Elementary (shown at the same scale):

On the density map, it looks like this:

Not all of that area goes to Hoover, of course; it couldn’t possibly fit. But the maps give you a good idea of why there are so many schools on the central east side: because that’s where the students are. Zoom out the see the broader east side:

You can see that it won’t be hard to draw attendance zones to fill the existing schools (which I’ve marked with green squares). What would be hard is finding 500 kids to put at each of the new elementary schools (the purple squares), which would take some serious gerrymandering. The solution is to keep the existing schools open and allow the new schools to start medium-sized and grow into their capacities.

School board members have said that their goal is to “put the schools where the students are.” It’s hard to take that literally, given where they’re building the new schools; it makes more sense to see those schools as an investment in the future. In the meantime, the student density remains concentrated around the existing schools. The district will need to keep them—including Hoover—open.

.

One way to see why that’s true is to look at the district’s student density map. It’s worth clicking on that link and perusing the whole thing. But here are a few highlights. First, here is an overhead view of the area around newly-built Alexander Elementary:

On the density map, it looks like this:

(The numbers represent number of elementary schoolers in each square; the more students, the darker red the squares are.)

Here is the area around the future site of the East Elementary:

On the density map, it looks like this:

Here, by contrast, is the area around Hoover Elementary (shown at the same scale):

On the density map, it looks like this:

Not all of that area goes to Hoover, of course; it couldn’t possibly fit. But the maps give you a good idea of why there are so many schools on the central east side: because that’s where the students are. Zoom out the see the broader east side:

You can see that it won’t be hard to draw attendance zones to fill the existing schools (which I’ve marked with green squares). What would be hard is finding 500 kids to put at each of the new elementary schools (the purple squares), which would take some serious gerrymandering. The solution is to keep the existing schools open and allow the new schools to start medium-sized and grow into their capacities.

School board members have said that their goal is to “put the schools where the students are.” It’s hard to take that literally, given where they’re building the new schools; it makes more sense to see those schools as an investment in the future. In the meantime, the student density remains concentrated around the existing schools. The district will need to keep them—including Hoover—open.

.

Saturday, June 13, 2015

The district will need Hoover even after the new schools open

Word has it that some of the families in and near Windsor Ridge are concerned that keeping Hoover open will prevent the district from opening Hoover East (which I’ll refer to here as the East Elementary School, to avoid confusion). It’s understandable that those parents would not want the rug pulled out from under them after being told that the new school will open in 2019 (though I would hope that they would sympathize with Hoover families who are threatened with the closure of their school, too). But they should not be concerned about keeping Hoover open. First, the East Elementary ship has sailed: realistically, it is too late to cancel that building even the district wanted to. Second, the district will continue to need Hoover even after the new school is open.

Some people have argued that the district can’t support Hoover and the new school, too. Financially, that is simply untrue, as I wrote here. But will there be enough enrollment to support that many schools? The answer is yes, for these reasons:

On paper, the planned 2019-20 east side capacity looks sufficient to handle the projected enrollment, even if Hoover is closed. But, as the district has repeatedly experienced, redistricting is not so simple. The two new schools each have a capacity of 500, but it is very unlikely that the district will be able even to come close to filling those schools at that time. Alexander, for example, is likely to remain underfilled for a good long while: it is simply going to be very hard to create districts that will put anywhere near 500 east side kids at that site, because the presence of several schools immediately north of it make the logistics so challenging. (And the district is even planning to add 100 seats of capacity to Grant Wood school, which is immediately to Alexander’s north!)

A similar problem is likely to arise at the East Elementary. There simply aren’t enough students in its immediate vicinity to fill it when it opens. The bulk of the student density is in the more central east side, in the established neighborhoods. It is easy to say “just rezone everyone,” but given the geographical distribution of students, the real-life logistics will be very hard.

But these are not terrible problems. It actually makes sense for those schools to open at fewer than 500 students and then grow over time. The whole rationale of building Alexander and the East Elementary was to remedy overcrowding in existing schools and to accommodate and spur expected development. If the district were to fill those schools to capacity at the outset, what would happen when the hoped-for development appears? With Hoover gone, the district would have no way to accommodate it, and would have to build more schools and additions—needlessly spending millions. It makes much more to sense to start those schools with enrollment under capacity and then grow into them.

If it’s true that Alexander and the East Elementary will open significantly below full capacity, then the overcrowding in the existing east side schools will continue, unless Hoover is kept open. Suppose the district puts only 325 kids at each of the new schools in 2019 (which is probably optimistic). Under the current enrollment projections, that would leave 2,635 kids to enroll at the remaining east side schools. But the capacity of those schools will be only 2,338. The most sensible solution to that overcrowding is to keep Hoover open.

And there’s another factor: the district’s projected enrollment figures do not include the kids in its preschool programs. That’s probably because preschoolers don’t have “attendance zones,” and can be shifted from one building to another if necessary. But they won’t just disappear, and it’s not feasible to send all preschoolers to the west side, even if there were space there. And (ironically!) preschoolers actually take up more space, because class sizes have to be smaller. So the actual expected east side enrollment is significantly larger than the district’s estimates make it appear.

Ultimately, a close look at projected enrollment should give Hoover families hope. It’s only a matter of time before the district realizes that life is much easier with Hoover open than with it closed.

.

Some people have argued that the district can’t support Hoover and the new school, too. Financially, that is simply untrue, as I wrote here. But will there be enough enrollment to support that many schools? The answer is yes, for these reasons:

On paper, the planned 2019-20 east side capacity looks sufficient to handle the projected enrollment, even if Hoover is closed. But, as the district has repeatedly experienced, redistricting is not so simple. The two new schools each have a capacity of 500, but it is very unlikely that the district will be able even to come close to filling those schools at that time. Alexander, for example, is likely to remain underfilled for a good long while: it is simply going to be very hard to create districts that will put anywhere near 500 east side kids at that site, because the presence of several schools immediately north of it make the logistics so challenging. (And the district is even planning to add 100 seats of capacity to Grant Wood school, which is immediately to Alexander’s north!)

A similar problem is likely to arise at the East Elementary. There simply aren’t enough students in its immediate vicinity to fill it when it opens. The bulk of the student density is in the more central east side, in the established neighborhoods. It is easy to say “just rezone everyone,” but given the geographical distribution of students, the real-life logistics will be very hard.

But these are not terrible problems. It actually makes sense for those schools to open at fewer than 500 students and then grow over time. The whole rationale of building Alexander and the East Elementary was to remedy overcrowding in existing schools and to accommodate and spur expected development. If the district were to fill those schools to capacity at the outset, what would happen when the hoped-for development appears? With Hoover gone, the district would have no way to accommodate it, and would have to build more schools and additions—needlessly spending millions. It makes much more to sense to start those schools with enrollment under capacity and then grow into them.

If it’s true that Alexander and the East Elementary will open significantly below full capacity, then the overcrowding in the existing east side schools will continue, unless Hoover is kept open. Suppose the district puts only 325 kids at each of the new schools in 2019 (which is probably optimistic). Under the current enrollment projections, that would leave 2,635 kids to enroll at the remaining east side schools. But the capacity of those schools will be only 2,338. The most sensible solution to that overcrowding is to keep Hoover open.

And there’s another factor: the district’s projected enrollment figures do not include the kids in its preschool programs. That’s probably because preschoolers don’t have “attendance zones,” and can be shifted from one building to another if necessary. But they won’t just disappear, and it’s not feasible to send all preschoolers to the west side, even if there were space there. And (ironically!) preschoolers actually take up more space, because class sizes have to be smaller. So the actual expected east side enrollment is significantly larger than the district’s estimates make it appear.

Ultimately, a close look at projected enrollment should give Hoover families hope. It’s only a matter of time before the district realizes that life is much easier with Hoover open than with it closed.

.

Thursday, June 11, 2015

Cause and effect (or How to rationalize a school closure)

The Hoover closure continues to be the decision in search of a rationale. The few attempts to articulate one have a distinctly post-hoc feel to them. One of them is the idea that “there are too many schools close together without enough enrollment to support them.” To back up this assertion, closure proponents cite the district’s latest enrollment projections. Those projections show a precipitous thirty-four percent drop in the projected enrollment at Hoover, which would have, at one point, as few as 199 students!

Looking at those projections, you would think that a big chunk of Iowa City’s east side—an area filled with residential homes—was on its way to becoming a ghost town. Or is there another explanation?

Take a look at what Hoover’s enrollment projection looked like right before school board voted to close it (click to enlarge):

Yes, just two years ago, the district projected that Hoover’s enrollment would remain well above its capacity for the foreseeable future.

This year, almost two years after the closure vote, the district’s new enrollment projections for Hoover look like this:

That year when the district says that enrollment would be only 199? Right before the closure vote, that same projection was 376.

So you be the judge: Did the declining enrollment projection cause the closure decision, or did the closure decision cause the declining enrollment projection?

.

Looking at those projections, you would think that a big chunk of Iowa City’s east side—an area filled with residential homes—was on its way to becoming a ghost town. Or is there another explanation?

Take a look at what Hoover’s enrollment projection looked like right before school board voted to close it (click to enlarge):

Yes, just two years ago, the district projected that Hoover’s enrollment would remain well above its capacity for the foreseeable future.

This year, almost two years after the closure vote, the district’s new enrollment projections for Hoover look like this:

That year when the district says that enrollment would be only 199? Right before the closure vote, that same projection was 376.

So you be the judge: Did the declining enrollment projection cause the closure decision, or did the closure decision cause the declining enrollment projection?

.

Wednesday, June 10, 2015

So shines a good deed in a weary world

Note to my school district: There might be something wrong with your “good behavior” program if it can work only when all the kids are materialistic and acquisitive and when no one gets any ideas about sharing the wealth. I’ve known some kids who disliked PBIS enough to simply say “No, thank you” when offered a reward ticket. This kid goes a step further toward addressing the utter amorality of this “good behavior” program.

It’s still far from ideal that kids who don’t get reward tickets should have to depend on the philanthropy of a kid who gets lots of them—what kind of society does this model?—but given the choices this kid faced, good for him. So creepy even to put kids in that situation.

.

It’s still far from ideal that kids who don’t get reward tickets should have to depend on the philanthropy of a kid who gets lots of them—what kind of society does this model?—but given the choices this kid faced, good for him. So creepy even to put kids in that situation.

.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)